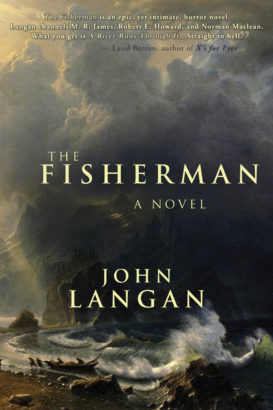

Hello, John. The Fisherman won This is Horror’s 2016 Novel of the Year award, and now it won the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in a Novel. Congratulations, it’s all definitely well deserved. At the end of the book, you indicate that the birth of The Fisherman was an unusually long process. What was it that finally led to its completion? Did your general conception of the story change from the time of the beginning of writing to the time of finishing it?

Thanks very much! That’s a great question. Certainly, I had been thinking about completing the novel for years, and certainly, my wife and my agent had been encouraging me to do so for about as long. What caused me to commit to bringing the narrative to a close was the knowledge that my good friend, Laird Barron, was going to be coming to stay with me and my family as he relocated to the east coast of the U.S.. Even when it’s a friend, the addition of someone else to your household is always a bit of a disruption, and I decided that, if there was a time to sit down and finish The Fisherman, it was before Laird arrived. As it turned out, I didn’t complete the book until after Laird moved in, but my writing had gathered sufficient momentum to carry me through to the end.

As for my conception of the book: I would say that stayed largely the same; although the middle section grew beyond what I had thought I would do with it when I started. As the narrative progressed, I had the thought of curtailing it, of letting my group of heroes go off to do what must be done, but remaining with the people waiting for them to return. As it were, most of the action would occur offscreen. I rejected that idea, largely because of advice the great Jeffrey Ford had given Laird when he was writing The Croning. “You’re going to feel the urge to play it safe,” Ford said. “Fight that urge. Go nuts.” Laird followed that counsel, and I decided I would, as well.

“Some things are so bad that just to have been near them taints you, leaves a spot of badness in your soul like a bare patch in the forest where nothing will grow.” A story whose words “stuck with” the narrator. A reservoir whose waters cover something that “prowls” the narrator’s brain. Reference to the Catskill Mountains. An ominous figure in the past concerned with bringing back the dead, surrounded by the most baleful rumors. A rhetoric, phrases, names, and tropes that cannot not ring a bell for an avid Lovecraft reader. What is your relationship as a writer and as a weird fiction aficionado to Lovecraft?

My relationship with Lovecraft is one that’s steadily grown as I’ve gotten older. When I was younger, I read more about him than I did of him. I read The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath in my early teenage years, but that left me cold. It wasn’t really until I was in college that I began to make my way through Lovecraft’s work; stories such as “The Call of Cthulhu” and “The Dunwich Horror” impressed me a great deal—although they didn’t fill me with the desire to imitate them. It was more a case of, I respected what Lovecraft was trying to do in them, and that respect grew as I read more in Lovecraft’s work. I wound up writing a reasonable amount of literary criticism about Lovecraft, particularly his influence on other writers. Most of what I wrote was presented at the annual H.P. Lovecraft Forums at SUNY New Paltz. A few pieces, on Lovecraft’s influences on Fritz Leiber, Thomas Ligotti, and Stephen King, have appeared in print over the years. I also have about a one hundred and sixty page, partially completed manuscript that considers the effect of Robert Browning’s “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” on a number of Lovecraft’s stories. It’s a very idiosyncratic work of scholarship that I doubt will ever see the light of day; despite which, I hope to finish it some day.

In terms of my relationship to Lovecraft as a writer, while I’ve certainly appeared in enough Lovecraft-inspired and -themed anthologies, I don’t see myself as participating in any major way(s) in the Lovecraftian tradition. Indeed, whenever I begin working on what’s supposed to be a Lovecraftian story, I find myself heading in the direction of the mundane, so that stories such as “The Shallows” and “The Supplement” seem to me as much informed by the work of writers like Raymond Carver and Richard Ford as they do Lovecraft. I’m not certain why this should be; possibly, it’s because I want to bring the gigantism that’s part of Lovecraft’s aesthetic down to a more human level.

Friendship, dealing with the loss of loves ones, struggling with guilt, moving on after an ordeal—universal questions of human existence, all of them markedly present in The Fisherman. Can supernatural horror fiction provide anything unique to the representation of these phenomena and problems?

I think every story, in every genre, offers the reader something unique, namely, its writer’s particular approach to its material. This is no small thing, and should not be discounted. In the case of supernatural horror fiction, the writer has the opportunity to employ tropes and situations that allow the abstract to become literal. In so doing, the genre gives to what can feel like very nebulous and intangible psychological states a physicality, a tangibility, which allows them to be approached in very direct terms.

Laird Barron characterized The Fisherman as “epic, yet intimate,” which, in my opinion, is a splendidly fitting description. If you had to describe the novel in one phrase, what would it be?

I’m not sure I can better Laird’s description; though I would hope readers find it resonant, as well.

The character of the Fisherman was originally a Hungarian man whose Turkish wife and children were slaughtered by Hungarian soldiers in the 16th century. Is there any special way this Hungarian reference got into the novel?

During my research on the construction of the Ashokan Reservoir, I learned that the men who worked on it had come from all over the place, including Hungary. This led me to the character of Helen, the woman who steps in front of a speeding mule team when she learns of her husband’s infidelity. I thought that, if she were Hungarian, the other women around her might not have known how to speak to her, which would have made her situation that much more unbearable, and led to her fatal act. George, her grief-stricken husband, searches out the character who will be known as the Fisherman in hopes of a remedy for his loss. I wasn’t certain why the Fisherman would grant George his wish, until I realized that George might be a fellow countryman. I already knew that I wanted the character of the Fisherman to have his origins in an experience of profound and shattering loss, and the reading I’d done of Hungarian history had included details of the slaughter of Turkish residents in the 16th century by Hungarian forces conducting a kind of ethnic purge. What if, I thought, my character of the Fisherman had been married to one of those residents, and what if she and their son had been among the murdered? That would make his decision to aid George more convincing, as well as rooting his quest to learn the dark arts in a more compelling story.

“Everything’ll have to be in its proper place. If there’s one thing I can’t abide, it’s a poorly put-together story. A story doesn’t have to be fitted like some kind of pre-fabricated house—no, it’s got to go its own way—but it does have to flow. Even a tale as coal-black as this one has its course.” These sentences of the narrator right at the outset of The Fisherman almost read as a passage from a treatise on creative writing or literary criticism. What makes a good story in your opinion?

I think the best stories are those in which something about the work compels the reader to keep reading. This may be the narrative voice, the style, the plot, the subject matter, or a combination of some or all of these elements. Some stories succeed based on the brilliance of their writing, some based on the irresistible force of their narrative movement, some based on both. There’s a way in which the best fiction seems very much itself, complete, as if it couldn’t have been constructed in any other way. Finally, the best stories linger in the mind afterward, don’t they?

Yet this description covers works as varied as King’s “The Boogeyman,” Barker’s “In the Hills, the Cities,” and Link’s “Stone Animals,” to name a few, so clearly, there are as many ways to write a good story as there are writers at work at any given moment.

You contributed to The Grimscribe’s Puppets and The Children of Old Leech, anthologies dedicated respectively to Thomas Ligotti and Laird Barron, two contemporary masters of weird fiction. What do the works of these authors mean to you?

I’ve also written about both Ligotti and Barron critically: Ligotti in an article examining the effect of Lovecraft on his story “The Last Feast of Harlequin,” and Barron in a number of reviews and appreciations. As is the case with Lovecraft, Ligotti is a writer I’ve appreciated more from a literary critical point of view than as a creative influence. I can remember reading the mass market paperback edition of Songs of a Dead Dreamer shortly after it appeared, and being struck by Ligotti’s deliberate use of a style and viewpoint that recalled the more baroque strain of the horror tradition: Lovecraft, of course, but also Poe and Clark Ashton Smith and even Ray Bradbury.

There was that same willingness to treat language as more than the vehicle through which the plot was conveyed, to foreground it as a significant, maybe the significant, element of the story. Later, when I was engaged in writing a series of conference papers on Lovecraft’s influence on subsequent writers, I read Grimscribe: His Lives and Works as part of the article I mentioned above. I didn’t keep up with Ligotti much after that, but it seemed to me that his work was crucial to the formation of certain writers: Michael Cisco, Jeff Vandermeer, Richard Gavin, and Simon Strantzas among them.

Laird is another story altogether. We published our first stories in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction one after the other, and from our first correspondence and then meeting, I’ve felt that Laird was the other brother I’d never known I had. Although our styles derived from different sources (his, Zelazny, Cruz Smith, Elroy, McCarthy; mine, Dickens, James, Howard, O’Connor), we were engaged in roughly the same project, namely, a response to the supernatural horror writers of our youth, Stephen King and Peter Straub and T.E.D. Klein. I was and remain struck by the tremendous commitment and integrity he brings to his writing: whether you love it or hate it, there is no doubt that he takes what he is doing with the utmost seriousness, and gives his all to it. I like to say that Laird is one of those writers who keeps me honest, by which I mean that, when I read something like “Hallucigenia” or “The Men from Porlock,” I think to myself, “Damn, I have to do better.”

The upsurge of weird fiction in our days is an obvious fact. What do you think is the reason of the increase in its popularity? Have you got any favorite contemporary authors in the genre?

In part, I think it’s due to the increase of small presses, which has allowed material that the increasingly conservative mainstream publishers are unwilling to take a chance on to see the light of day. For all its faults, I think the internet has allowed us to become aware of writers whose work might have slipped under our collective radar in the past. It also seems to me that many of the horror tropes of the 1970’s and 1980’s have infiltrated the wider culture, making their place of origin (slightly) more acceptable.

As for contemporary writers, there are more than I can remember at once. Laird Barron, of course, and Paul Tremblay, and Sarah Langan (who is no relation), and Stephen Graham Jones, and Michael Cisco, and Livia Llewellyn, and S.P. Miskowski, and Victor LaValle, and Kaaron Warren, and Gemma Files, and Sarah Pinborough, and Brian Evenson, and Dan Chaon, and Anya Martin—and that’s just off the top of my head.

What attracted you to writing fiction, and what drew you especially to weird fiction?

I suspect the full answer to this question is an essay, and not a short one. For me, narrative was connected pretty much from the start with drawing, which I loved to do. Indeed, one of my earliest memories is of having to write a story for my first grade class. It had to be a full page long, but it could be about whatever we wanted, and we were allowed to illustrate it. I wrote a story from the point of view of King Kong, who confronted and subsequently defeated Godzilla. I can still see the picture I drew. During my primary school years, I wanted more than anything to draw comic books, which extended the link between drawing and narrative. Then, when I was a freshman in high school, I read Stephen King’s Christine, and that was it: I made the jump to writing. (It probably didn’t hurt that my school had no art program to speak of.)

I think that storytelling is one of the fundamental human activities, one of the ways we understand our experiences as individuals and as members of a variety of larger groups. Weird/horror fiction offers a way to approach another fundamental aspect of our experience, namely, those moments when the solid ground on which we had thought we were standing drops out from underneath us, leaving us falling through space. Put another way, horror fiction is the voice of skepticism, questioning our received ideas about the world and how it functions. To paraphrase Herman Melville speaking about Nathaniel Hawthorne, “Horror fiction says NO, in a voice of thunder.”

What was your scariest horror experience ever?

I’m not sure what the absolute worst has been, but many of them have come through. My first viewing of David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly, which I watched on videotape, was so intense I had to stop the movie, stand up, and walk around the house before I was ready to continue the film. Some of the images in David Lynch’s work (I’m thinking here of Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire) have disturbed me in ways that are deep and profound.

In terms of fiction, I vividly recall how frightened Robert E. Howard’s “The Horror from the Mound” made me the first time I read it, also Stephen King’s The Shining. More recently, Laird Barron’s The Croning contained a long chapter that genuinely scared me.

You have published two novels and three short story collections so far. Have you as a writer got any preference to either short stories or novels over the other? What do you enjoy or consider as important in either a good short story or a good novel?

My work tends to run long, in part because I prefer to have room to develop my characters, so that whatever happens to them will linger in the reader’s mind afterward. (It’s probably also a consequence of having read more novels than any other literary form.) That said, whenever I can write something short that I think succeeds, I’m happy, because I find it difficult to achieve what I want to at that length. Whether short story or multi-volume novel, though, I think any narrative needs to draw in its reader, catch and hold their attention until it’s finished. If there isn’t something compelling about your narrative, right from the start, then it’s going to have a hard time finding an audience.

Some say a good story just emerges in the author’s mind spontaneously, and bursts out of him/her, others argue for a method of strict self-discipline and persistence in writing. Have you got any specific and effective methods of writing?

I think both views have some truth to them. At the outset, it seems to me, most writers begin with inspiration, with an urge to write something that springs from their love for a particular type of narrative. That may even be enough to carry the writer to the end of a few stories. Inspiration’s a tricky thing, though, and it doesn’t always show up when you want it to. If your goal is to write for the long run, then you need to develop other strategies. Specifically, you need to establish a decent, regular work schedule. As someone or other said, If the Muse is late to work, you start without her.

In practice, this means sitting down to write at the same time each day. I prefer early in the morning or late at night, because these are the times when my inner critic, the annoying editorial voice that tells me whatever I’m working on is garbage, is asleep. For an hour or two, I can work without having to worry about that faculty, which will be useful once whatever I’m working on is done. When I was first writing, I set myself a modest goal: one new page a day. I figured I could accomplish that much. I would begin each day’s work by rewriting the page I’d written the day before. This allowed me to correct any mistakes I noticed, to expand places it occurred to me to expand, and to slide back into the narrative. The big secret I discovered is that the secret to writing is writing. How often, in the course of working on a piece of writing—it doesn’t matter for what—have you found some new idea springing up in the middle of your writing, something you had no idea was going to appear in front of you? Rather than being a medium through which the pre-formed idea flows onto the page, writing is in and of itself a creative act; if you like, it summons the Muse to you.

Two more insights: you have to have patience, and you have to keep working.

Thank you for the interview.

Thank you so much for thinking of me.